The following is an excerpt from my forthcoming book, Affective Teaching: The 9 Positive Emotions that Build Community, Engage Attention, and Motivation Students to Take Action ©

Humans have a problem with logic. I don’t mean that we are logic deficient. It’s other way around: We often overweigh the impact of logic to drive decision making. We make logical pro/con lists comparing all the features and reviews of which car to buy…but ultimately, we sit in one and it feels right. We get attached for life to sports teams filled with strangers we’ve never met (or get attached to whole teams just because we know or have met one of their players). We have to automate retirement investments because we can’t trust ourselves to make the logical choice each month to save money for the future. Logic may inform our decision-making, but it doesn’t drive decision making. Conversely:

Emotions don’t just support decision making. Emotions ARE decision-making.

Consider the magnitude of this statement from the lens of our students. Everything they choose to do (or not do) in our classroom hinges upon their emotional states. Emotions decide whether they show up to class – and whether they show up on time or late. Whether they smile, grunt, or ignore us as they enter our room. Whether they dive into the bell work or stall (and what degree of effort they give with either decision). Whether they raise their hand to answer a question, ask for help, or try their daily escape to use the bathroom. Whether they listen, daydream, or ruminate. Whether they sneak a look at their smartphone, doodle on their notes, or disassemble and reassemble their pen to pass the time.

The emotions experienced in a classroom drive the learning outcomes.

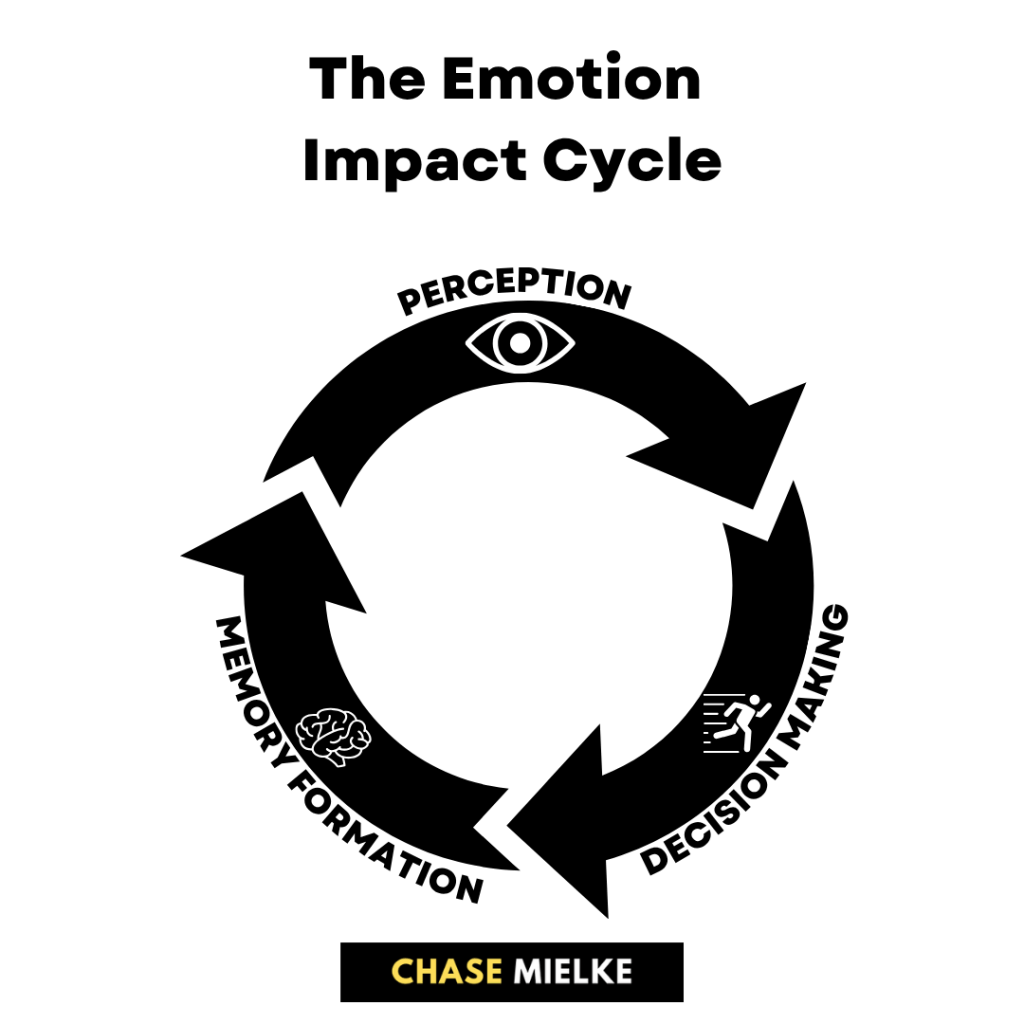

How students feel will influence every element of their learning experience: How they perceive their experiences, the decisions they make, and the memories they form.

If we want better academic outputs, then we need better emotional inputs.

We need to understand how emotions shape every element of the learning experience: perception, decision-Making, and memory Formation. It’s time to understand the Emotion Impact Cycle

The Emotional Impact Cycle™

- Emotions affect perception

Before students even step into your learning space their emotions are already shaping their perception. Do they see your class as a massive, challenging mountain to climb – with countless barriers slowing them down? Or do they see it as a fun, adventurous climb with paths to guide them? Emotional states will decide their perception.

Perception of difficulty

Put bluntly, there’s no such thing as objective perception. Studies show that sad emotions influence people to perceive a hill as much steeper: the sadder you are, the steeper the hill looks. Induced fear at the top of a hill makes people Acrophobics (fear of heights) aren’t just be wimps about heights – they might literally perceive heights as larger compared to others.

Perception of others

Emotions affect our perceptions of others as well, even if the emotions are influenced outside our conscious awareness. When study participants are exposed to positive images outside their conscious awareness, they are more likely to view a neutral face as positive. Priming negative emotion increased likelihood of viewing the neutral faces as negative. Whether students view you as impairing or empowering their growth might do as much with their emotions as your actions.

Perception of time

Is time flying with fun or lagging with monotony? Emotions decide even how we experience something objective like time. Approach-motivated emotions like curiosity, belonging, and joy speed up the perception of time; avoid-motivated emotions like fear, embarrassment, or anxiety slow it down.

Perception of perspective

Ever been annoyed by students griping, “When will I ever need to know this!?”? We often mistakenly combat this with a logical explanation of the importance of our content. But how students view the bigger picture of learning is an emotional experience, not a logical one. Emotions are at the helm of global versus specific views. Being induced with positive emotion causes individuals to view a more global view (e.g. I see how this writing practice is making me a better thinker). Negative emotions narrow our view (e.g. This writing practice is dumb and a waste of my time).

Objective perception is a myth. “[W]e do not come to know the world through only our external senses — we see the world differently when we feel pleasant or unpleasant.“

- Emotions affect decision-making

It’s 1:15 p.m. and I’m in the staff break room, staring at a dried-out quartered hunk of donut. It sits among a half dozen other mangled donuts – chunks colleagues have picked and sliced and pawed at through practices of self-restraint or loving donut chaos.

A logical voice in my head, faint and desperate, pleads: This donut will never satisfy you. These donut calories are hollow and will make you feel worse later. It’s a day old. It’s dry. It’s not even a flavor you particularly like (powdered with jelly? Blech). But the logical voice doesn’t know I’ve already made my decision – possibly before I even opened the grease stained box of decrepit donuts. I begin mindlessly eating the donut shard.

Why did I make this irrational choice? Because emotions make decisions.

The ancient parts of our brains have a master priority: Survive. And how do we survive? Maintain an effective body-budget balance. If you want to strip life of all its pomp and romanticism, our existence is simply trying to maintain the energy required to keep chugging along. At every moment we are consuming calories – pumping blood, breathing, thinking, digesting food, exerting motion. If we continue to consume more calories than we have, we’ll eventually shut down (i.e. kick the bucket). Therefore, every decision we make is rooted in predicting and responding to our moment-to-moment energy needs.

When I hovered over that donut box, my energy needs, exhausted by hours of teaching, already primed my decision. Walking into the break room laid the foundation of prediction (sometimes the insurance company donates donuts…). This prediction cued the emotion of curiosity, encouraging me to approach. The sight of the box ignited craving as my brain recalled previous delicious donut indulgences. By the time I opened the box and logically thought, “These donuts are old and gross,” the game was already over: My body, driven by my energy-expending-and-expecting brain, was reaching for the donut. It’s no coincidence that the root of the word “emotion” – the Latin “movere” – is the same root that makes up motive, motivation, and move. Emotions drive decisions.

This isn’t to say logic doesn’t matter – just that emotions, driven by predictions and responses to energy needs, have the final say. Logic is the spark, but emotion is the fuel. Examples abound of how our decisions are rooted in emotion, not logic.

Look at, watch, or listen to any advertisement and you’ll notice the priority of shifting your emotions. Even the presentation of statistics is cuing emotions. 9 out of 10 dentists agree? Well…I trust and feel reassured by their expertise. We are biased toward positively framed probabilities: Folks are more likely to undergo a medical procedure when told “9/10 survive” versus “10% of people die.” The logic is the same – but the feelings we get from the framing have the final influence. And half of early deaths in America are caused by choices that defy the logic. We know we should eat better, not smoke, not drink, alcohol, and exercise more. Yet, the logic often can’t override our emotional draw to this risky behaviors.

Closer to home, we must acknowledge that our feelings create bias that can affect real learning outcomes of students. For example, multiple studies have demonstrated that teachers give worse grades to students they have negative perceptions of – including based on their race, weight, and gender. Experimental studies find that priming a teacher with positive emotions biases teachers to give better grades and negative emotions biases them to give worse grades. Even simulated reputations bias us: Hearing that a student is unmotivated in one subject biases teachers to give them worse grades in a different subject. Frightening to consider that the academic achievement of kids may hinge on the emotions of their teachers.

- Emotions affect memory formation

My dog is a genius who understands the English language. That’s probably an overstatement; she’s yet to fully engage me in a dialogue about the greatest literary masterpieces of the 20th century. But she understands a few words:

- Bad

- Walk

- Treat

- Ride

- Here

- Sit

- Shake

- Down

Even hearing the word “here” from three rooms away sends her into frantic excitement – jumping on the couch, scrambling to look out each window, barking with joy at the prospect of a visitor. She’s even improving her spelling skills, fully aware of what “W-A-L-K” means.

We all know she doesn’t understand “here” to mean “an adverb used to represent relative location that can also function as an adjective following a demonstrative noun or pronoun.” She’s not that nerdy. She simply understands that the sounds of “here” mean we might have a visitor, which is an experience saturated in emotion. She understands the words tied to emotions because emotions can make or break memory formation.

Everything we do as teachers is designed to help students store and retrieve memories. Unless we want kids to live their entire lives in our class (which some of them seem to want to), our goal is to help kids create a rich, transferable memory bank of skills and concepts they can use in life beyond our classrooms. Much of traditional schooling is helping students build memories. Historical dates and their significance. Math formulas and their application. Scientific facts and their effects. Names of teachers and their pet peeves. Due dates and definitions and plots and procedures.

But there’s a huge hurdle that gets in the way: Brains are built to forget. This happens at multiple levels. First, much of what we sense gets ignored. Reports say we are exposed to nearly 11 megabytes of information each second – yet we only process 40-50 bytes at a time. From there, much of what makes it into our working memory is limited, with most of us only able to remember 3-5 chunks of information at a time. The transfer into short-term memory has a further shelf life.

So much of what students experience in school gets forgotten because If we retained every piece of information we experienced, we’d overwhelm our minds much like a computer slows down when its memory is filled. To avoid bogging down our brains, our minds are built to prioritize and retain only what’s significant.

How do we decide what’s significant? Three main ways:

1. Repeating and/or applying the information (e.g. rehearsing a PIN over and over as you type it into your password recovery form);

2. Connect new info to established memories (e.g. mnemonics like HOMES and Never Eat Soggy Waffles function off this);

3. Taking the learning with emotion (e.g. Playfully acting out a scene to recall plot details, using mildly competitive review games to add)

All three methods work, but emotions are the shortcut. If we imagine memory formation to be creating a path in an overgrown jungle, repeating information is like creating a path with a small machete. Hacking once isn’t enough. We have to continually cut through, over and over – not just at the time of learning, but distributing the repetition over days and weeks.

Using emotions, though, is like a bulldozer for creating neural pathways; If the emotion is strong enough, the memory path can be available long-term. Emotional states drastically improve our ability to store and retrieve memories. For example, feeling curiosity increases focus of attention and leads to higher performances on post tests and transfer tests. Facilitating surprise through novelty helps brains explore more and primes our learning systems to store and retrieve memories better – in both adults and children. Even stress, at mild and acute levels, can facilitate stronger learning and memory formation. The type and intensity of the emotion while learning may be the greatest decider of whether and what we can recall after the learning.

We don’t live in a logical world, my friends. Sure, logic exists — but it’s often along for the ride as emotions take the wheel. Emotions shape our perceptions which dictate decision-making which influence memory formation (which, in turn, affects perceptions again). Emotions drive the learning. The more we accept that reality, the more we can be strategic, intentionally and proactively, to facilitate better emotional inputs to generate greater academic outputs.

| Apply It! Collect some perception data. Find ways to collect feedback from students. Have them respond to prompts like, “Scale of 1-10, how safe do you feel asking questions in class (1 = ‘I’m too afraid to ever ask things’; 10 = ‘I have no fear asking something’)” Or, make them content specific: “Scale of 1-5 how confident do you feel going into this next writing assignment?” Check your own bias Reflect on the biases you bring into grading your students. Well-created rubrics can help. Or, invite unbiased second opinions, like a willing colleague or ChatGPT. Check out Sarah Gonser’s piece in Edutopia for other ideas. I’ve found it helpful to glance through all student work before assigning any sort of evaluation. Do a decision “RePlay-Doh” At the end of the day, reflect on a decision you made and analyze the context. What do you think was going on with your body-budget? Were you tired? Hungry? Stressed? Well-rested? Were other people present? If so, how did their presence influence your decision? What if they hadn’t been there (or, if you were alone, how might your decision have been different if others had been there)? I call this a mental “RePlay-Doh”: Kneading around a scenario to see how different emotions or contexts make our decisions “take shape.” Infuse an emotion Look at your next teaching task — or one of your more challenging ones — and ask, “Which emotion, if I facilitate it, would enhance the learning experience?” Does a challenging task need a little play and joy to help students stop being so self-conscious? Would curiosity help engage their attention? Will it be key to establish feelings of psychological safety before diving into a collaborative learning activity? Don’t wait for emotions to derail the lesson — create emotions to direct the lesson. |

If you’re not sure on that last one — which emotion to infuse and how to do it — don’t stress (unless that motivates you). That’s the work of my next book, coming your way soon: Affective Teaching: The 9 Positive Emotions that Build Community, Engage Attention, and Motivate Students to Take Action.

So, you can stay tuned as I continue to share more excerpts. Or, you can let an emotion compel you to message me and we can nerd out together sooner 🙂

Copyright Chase Mielke 2025

Leave a reply to Kay Parker Cancel reply