This post is an excerpt from my book, The Burnout Cure: Learning to Love Teaching Again

The data isn’t good about New Year’s Resolutions: Though many people set them, a HUGE majority fail. Despite the low odds of success, I’m still a big believer in setting goals — because striving for goals, even if we fail, is linked to greater well-being. And striving toward goals in one domain of life boosts happiness across other domains (Wiese & Freund, 2005). A goal beyond the classroom can translate to being a happier, better teacher in the classroom.

Before you write down “Goal: Be happy” and call it a day, recognize that not all goals have the same effect. If you’re chasing the wrong route to well-being, you may attain an ill-crafted goal but still feel dejected.

We need to understand how goals can be guides for our well-being—leading us in the right direction of both success and satisfaction. In fact, we can use the acronym GUIDES as a mental checklist to ensure that our goals are more likely to increase well-being.

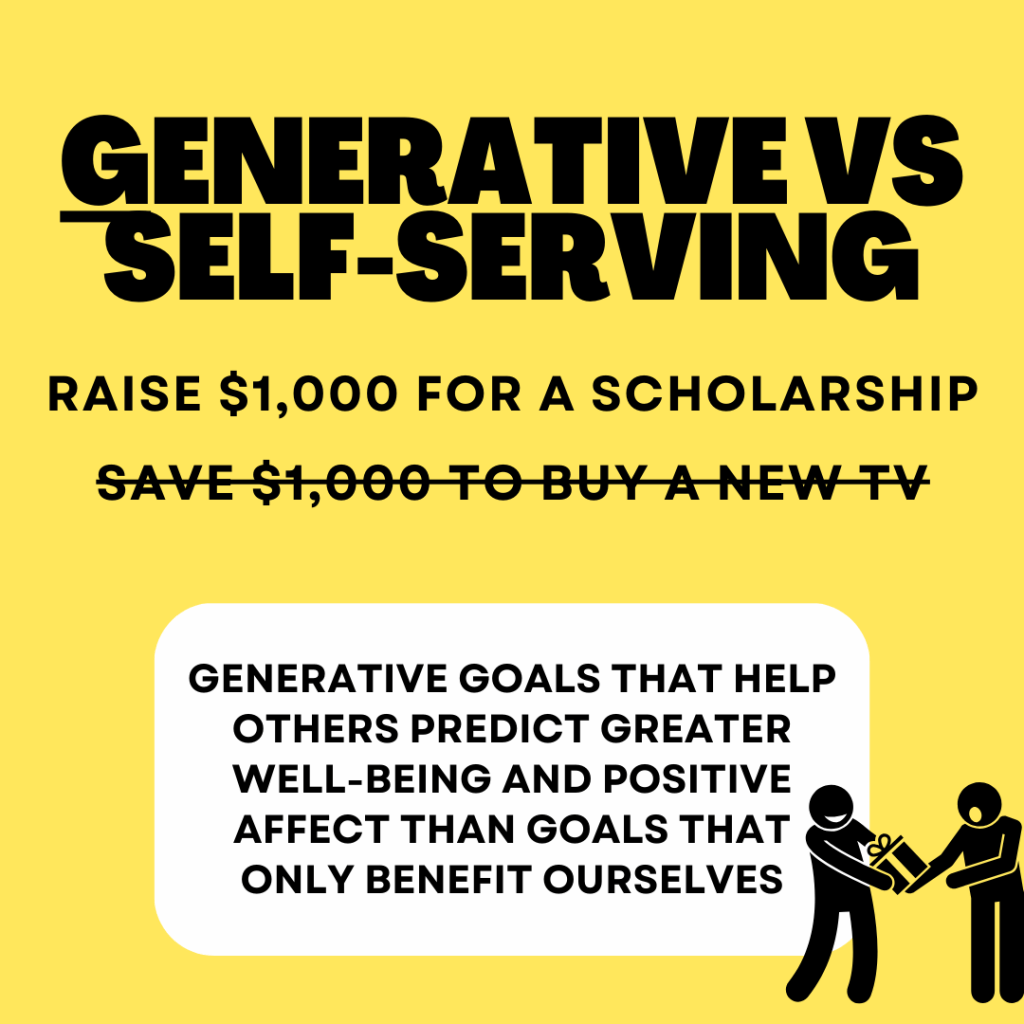

Would I be happier buying a 415-inch HDL-LCD-XYZ TV with surround sound or giving money to some kid I’ll probably never see again? Although a new entertainment system would be nice, goals that “give” yield greater well-being.

Researchers have found strong links between well-being and goals that are aimed at helping others. Generative strivings, which aim to provide something positive for other generations or other people, predict well-being and higher positive affect compared with striving for status and power goals (Emmons, 1991). In national samples, higher levels of generative motives, behaviors, and traits contributed to heightened levels of psychological and social well-being (McAdams, de St. Aubin, & Logan, 1993; Ryff, 1989).

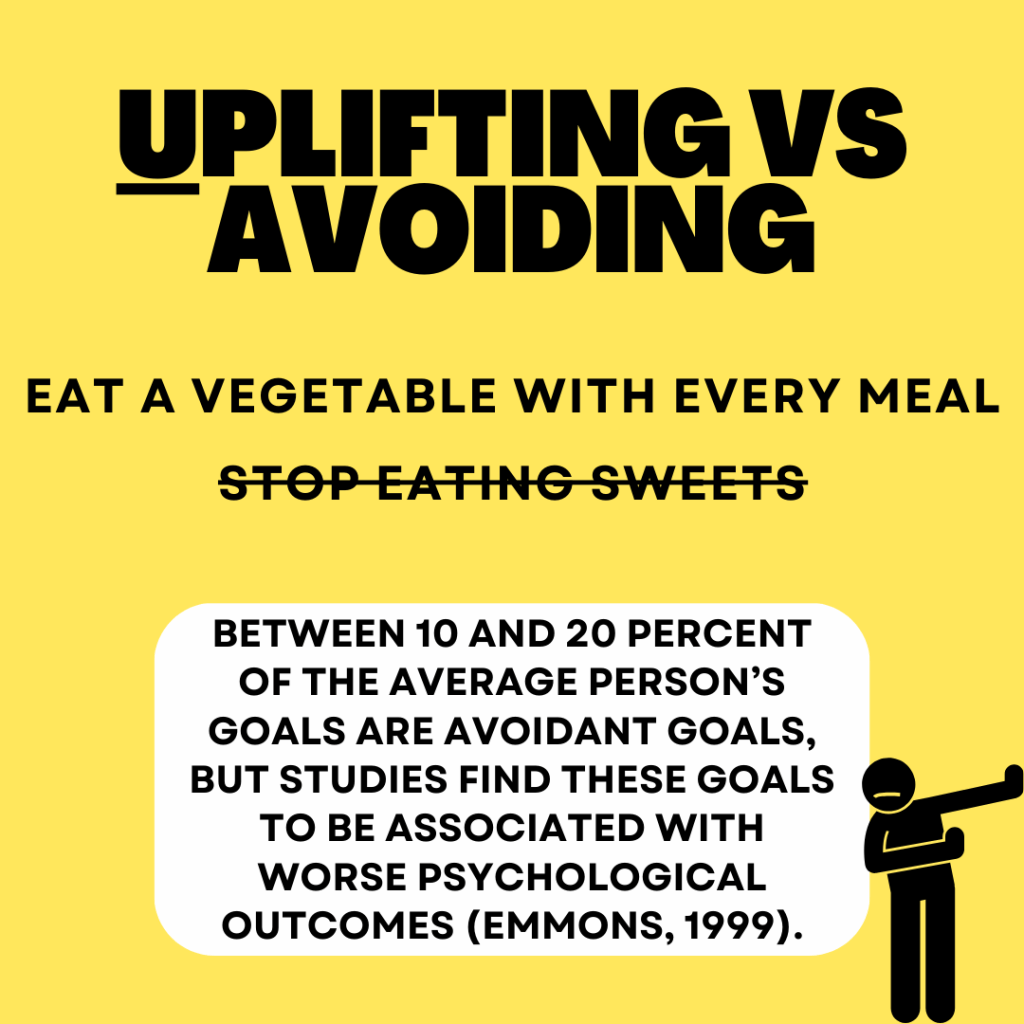

Uplifting goals are ambitions framed around positive incentives or experiences, compared to avoidant goals, which focus on preventing negative consequences. One might think that how we word a goal doesn’t matter, but studies show that our framing does matter. Rather than setting a goal to minimize or avoid bad things, frame your goals to increase good, positive actions.

Between 10 and 20 percent of the average person’s goals are avoidant goals, but studies find these goals to be associated with worse psychological outcomes (Emmons, 1999). Medical patients, for example, who set avoidant goals were less likely to attain those goals, felt a greater sense of external pressure to achieve them, and had more physical health complaints over time (Elliot & Sheldon, 1998).

And avoidant goals don’t only affect our success and well-being; they can also affect relationships. In a sample of married couples, marital satisfaction was negatively related to how much a spouse framed goals as avoidant instead of uplifting (King & Emmons, 1991).

“If every one of your colleagues were rated ‘highly effective’ on their evaluation, would that change your motivation?” My principal posed this question to me and another teacher I greatly admire. I didn’t need to think long about my answer. Neither did my colleague.

“Not one bit.”

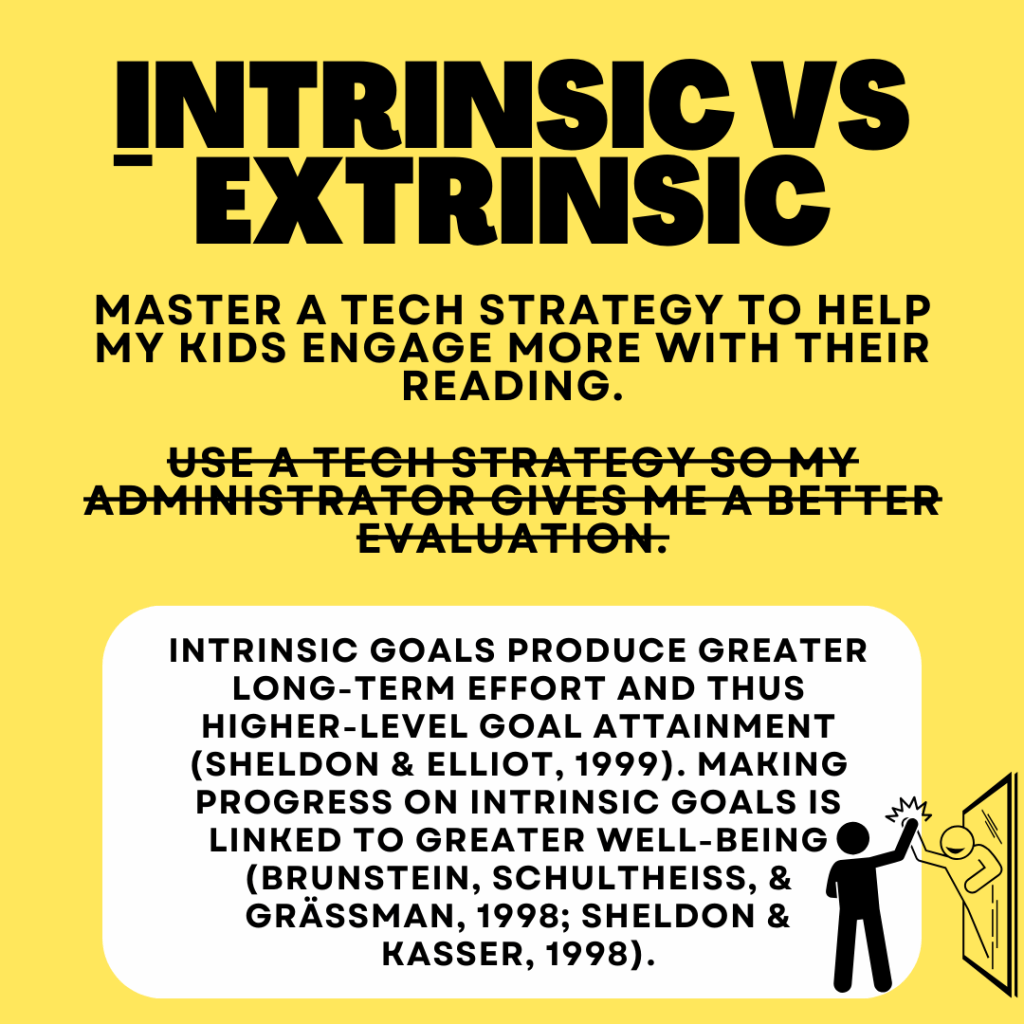

The question was rooted in a common, yet fraudulent, idea about motivation and goal setting: carrots and sticks will help us achieve more and thus make us happier. The glaring issue with this mode of thinking was apparent in our answer: our intrinsic standards, values, and goals are what drive us. Think about your own experience. When has a “point boost” on an evaluation made you happier than having a meaningful teachable moment with a student?

Intrinsic goals not only engage deeper motivation; they also produce greater well-being compared to extrinsic goals. Studies show that intrinsic goals produce greater long-term effort and thus higher-level goal attainment (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999). Making progress on intrinsic goals is linked to greater well-being, whereas progress on extrinsic goals has no relationship to our happiness (Brunstein, Schultheiss, & Grässman, 1998; Sheldon & Kasser, 1998). Focusing on extrinsic goals is also associated with higher anxiety, depression, narcissism, and physical illness (Kasser & Ryan, 1996). As a result, the most effective goals and feedback are framed around what intrinsically motivates someone, whether teacher or student, not the threat or pressure of assessment and evaluation.

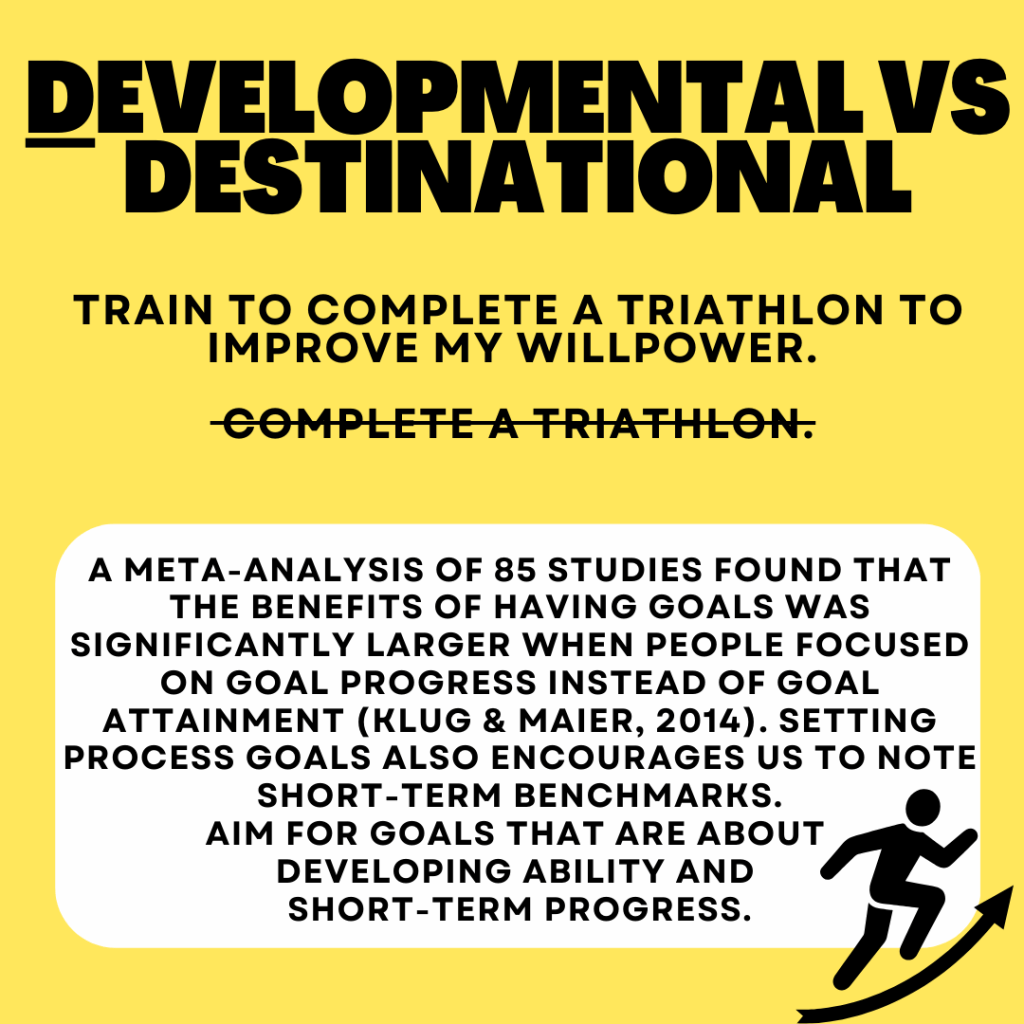

Have you ever solved the Rubik’s Cube? Not this guy. I’ve been working at a Rubik’s Cube on and off for more a year. Someday there will come a moment when that aggravating block will be back in its original color-coordinated form. Will that moment boost my happiness for months to come? Probably not. My ambition for taking on that block of fury isn’t about the destination. It’s about developing one of my personal weaknesses (spatial reasoning) into a skill. It’s about minor victories.

We should have long-term goals that drive us. But once we set the destination, we should shift our focus to the short-term steps and the process along the way. Focusing too much on the destination or goal as a source of happiness may let us down.

A meta-analysis of 85 studies found that the benefits of having goals was significantly larger when people focused on goal progress instead of goal attainment (Klug & Maier, 2014). Setting process goals also encourages us to note short-term benchmarks. Aim for goals that are about developing ability and short-term progress.

You’ve seen the Black Friday videos—people mauling each other for the latest must-have fuzzy robot. You’ve seen the growing lines outside electronics stores, extending like mold. People are obsessed with stuff and are willing to go through gauntlets for shiny things. Worse than the time wasted in line is a simple fact:

Spending on things is not as beneficial to our well-being as spending on experiences.

Sometimes our goals revolve around acquiring material possessions or things to bring us joy (and anyone who uses retail therapy understands the mood boost from a new purchase). However, in the long run, money spent on experiences yields greater gain for our life satisfaction (Hajdu & Hajdu, 2017). The rationale is multifaceted: experiences typically don’t elicit as much social comparison as possessions, they often allow us to share with others, and they’re often a more meaningful part of our identity (Caprariello & Reis, 2013). People even derive more happiness anticipating an experience compared to a possession (Kumar, Killingsworth, & Gilovich, 2014). If you’re feeling the need to stand in line for a ridiculous amount of time, stand in line for theater tickets instead of animated toys. And make sure your goals are more about doing rather than having.

Many years ago, one of my student groups held a fundraiser selling T-shirts with a simple slogan: Spread Positivity. Our community loved them, and in merely two weeks the group raised more than $500 for intentional acts of kindness. Although the shirt sales were a success and the message is truly a great one, the effects of the slogan may be subpar. “Spread a Smile” might have generated a better mission for the T-shirt owner—at least according to a series of six Harvard studies.

The studies compared concretely framed goals, like “Make someone smile,” to abstractly framed goals, like “Make someone happy.” Participants who set concrete goals felt happier upon attempting their goal compared to the abstract-goal group (Rudd, Aaker, & Norton, 2014). The rationale was that the concrete goal was easier to verify in the mind of the goal-setter. The abstract goal, on the other hand, may have created a larger sense of disappointment as the individuals wondered whether they really did make someone happy. Without a concrete piece of evidence, our expectations might cause an upward comparison and leave us disappointed.

Not only does setting a specific goal give us a better sense of satisfaction when we hit it; setting concrete goals, especially specific subgoals within a big, long-term ambition, can increase our likelihood of success (Locke & Latham, 2006).

Rather than “Improve my health,” set a goal like “Complete a 5K.” Rather than “Make someone’s day,” try something like “Buy a meal for someone.”

So, will GUIDES be a surefire way to accomplish all your goals this year? Probably not. But, in setting goals based on this research — and in striving for them even if we might fail — we’ll still develop greater well-being.

Stretch, seek, grow, and strive, my friends.

Leave a comment