The Educator Happy Hour Podcast summer book study choice is already giving me insights that are making me a better educator and parent.

Irony 1. We overprotect the real world and underprotect the virtual world

“Mom, you cool if I go interact with complete strangers without supervision tonight — maybe stumble upon some porn or explicit content not meant for kids?” If I had asked my mom this as a teenager she, like every parent, would’ve surely said no. Except she, like probably every parent, said yes…in a sense.

As a teenager, I was given structure, boundaries, and rules in the real world. But I explored the internet world with little, if any, guidance or restriction. This was the late 90s. Sold as “the gateway to the future,” the internet metastasized into modern homes with little caution or understanding of its scope and power.

Now, I’d like to think I turned out fine. But I consider what I could access on the internet versus what I could access in the real world. If adults allowed their kids to take unsupervised strolls through malls with pornography, violent content, and ambiguous strangers asking for our A/S/L, folks might call CPS for negligence. But this is exactly what many of us were allowed to do via the virtual world.

I was struck by Haidt’s line, “While parents worked to eliminate risk and freedom in the real world, they generally, and often unknowingly, granted full independence in the virtual world” (9).

Our care for kids has been ironic: we often overprotect in the real world, yet give our kids access to plenty of dangers in the virtual world.

Smart phones with open internet access. Social media accounts that intentionally target human addiction patterns — and have an un-enforced “minimum age requirement” of just 13. Video games streaming strangers’ voices.

No doubt, restrictions, awareness of dangers, and coaching kids on the pros and cons of virtual spaces is better than when I grew up. Yet, the irony of overprotected real world versus underprotected virtual world parenthood is still abounding.

I’ll discuss the virtual world more in the future. For now, I want to focus on the overprotection of the real world — which leads to another irony.

Irony 2. We are more fearful of a more mundane world

I remember once reading a question: “How come millennials brag about childhoods of roaming neighborhoods until the lights came on, yet coddle their own kids?” The question is valid. In just a few generations, kids are more restricted to roam. You can see maps depicting this.

Someone’s answer to this question, though, was poignant: We’re the first generation to have a firehouse of information shoved down our throats every day. 24/7 news cycles; bottomless social media feeds; the fact that any story, regardless of its vetting process can get equal access to our minds — these are the features of modern life and parenthood.

Yet here we have another irony:

Our media is more sensationalized and negative, even if our society might be safer.

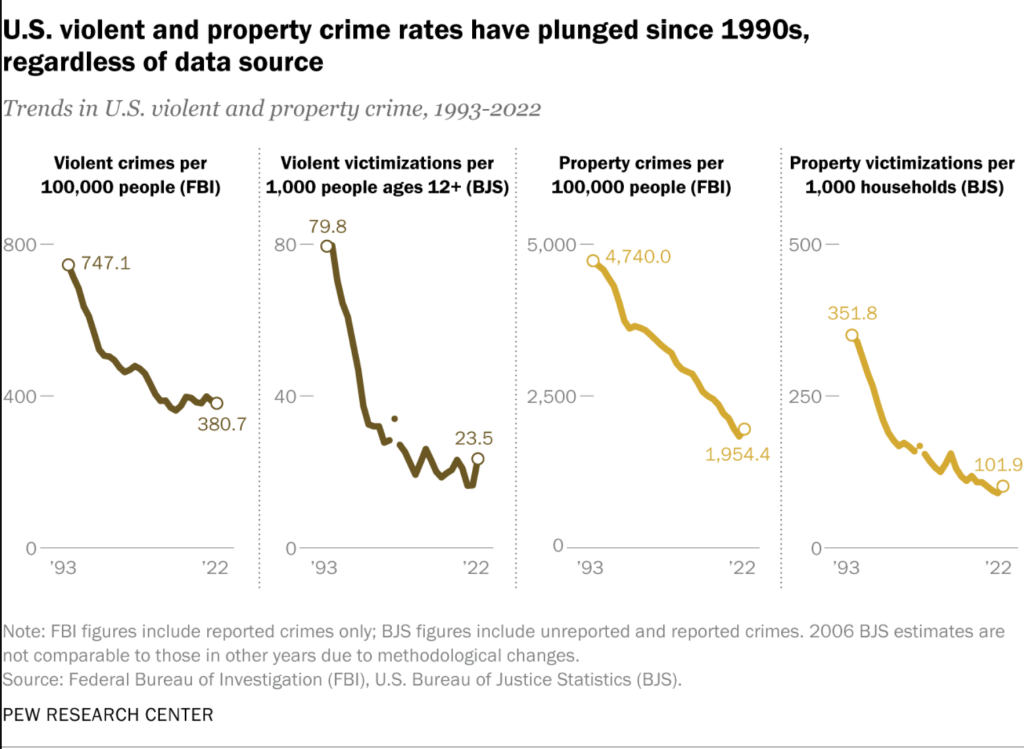

The debate of societal safety is a complex one — and no one data point gives a complete picture. Nevertheless, when looking at trends of data across various sources, like Pew’s analysis of FBI and BJS data, it’s hard to ignore a downward trend in violent crime:

Yet, “In 23 of 27 Gallup surveys conducted since 1993, at least 60% of U.S. adults have said there is more crime nationally than there was the year before, despite the downward trend in crime rates during most of that period.”

We all have negativity bias. Our brains our wired to pay attention to and remember negative, threatening information more than positive. Notice the threats first, so you survive to get the treats later. Many of us remember this literally when one sensationalized news story of a razor blade in a Halloween treat prompts hysteria to check every treat.

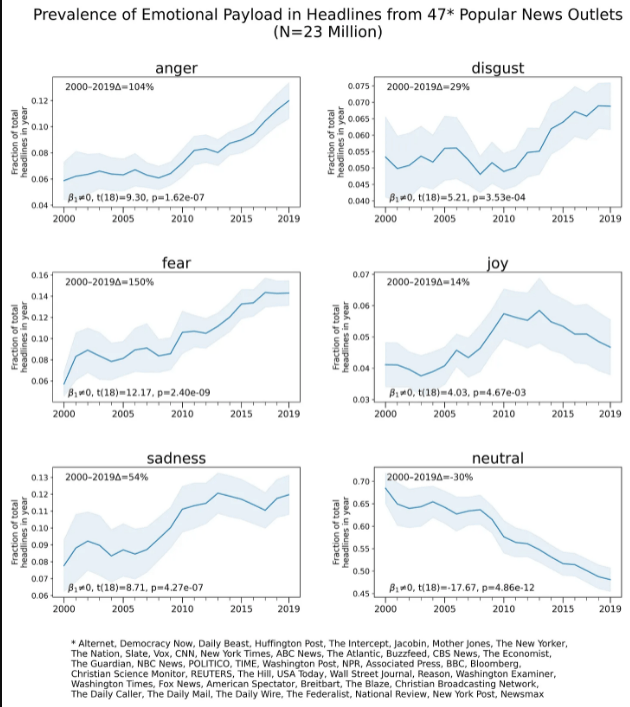

But back to that firehose of information. A 2022 study of 23 million news headlines across major news organizations found an increase in negatively charged words in the last two decades, even if trends point to a more positive world:

What’s more: The more negatively charged words placed in the headline, the higher the click rate of the reader. Put differently, in an attention economy, news outlets up the negative emotion to up the profit.

Our negativity biases are satiated by our news “feeds”

So the question lingers: Are we overprotecting our kids because our world is more dangerous? Or because we perceive our world to be more dangerous, even if it’s safer?

Yet another irony, I’m realizing, lies in the fact that, even if you accept that the real world is safer for kids, knowledge alone isn’t power

3. A surplus of facts doesn’t always lead to a shift in action

The irony of the ideas above are not new to me — I’ve seen them play out in my life as an educator and parent. I’ve seen students of helicopter parents have unrestricted access to smart phones. I’ve heard fearful discussions about news stories and how unsafe society is, despite real data to back the claims up. I also know firsthand that childhood anxiety can be exacerbated by overprotective parenting.

And yet, despite knowing better, I don’t always do better. I still have been overprotective of my own young kids in the real world. I’ve let my fear get in the way of their natural, necessary, and healthy desire to explore the world, to take risks, to get cuts and scraps, to make mistakes.

Information is only as powerful as our volition allows.

The biggest shift for me, upon diving into The Anxious Generation has been turning these ideas into action. And every day I’m challenged to know the balance:

How to couple healthy structure and support with healthy risk and independence

How to safeguard them in virtual spaces yet loosen my control of their real world

How to be informed of risks yet a rational raiser of kids

Knowledge is the start of change. But it doesn’t do anything unless we put the ideas into practice — until we acknowledge our own anxieties and embrace risk.

Now what?

You’ll no doubt draw your own conclusions on these ideas. For me, I’m focusing on my tendency to overprotect my kids in the real world. I’m committing myself to allowing the kids I care about daily Structured Freedoms.

Here’s an example:

My brother recently rebuilt my old go-cart for me. As kids, this redneck go-cart was one of my greatest sources of joy. My brother and I would tear around our yard chasing each other at 20 miles an hour, drifting and skidding around corners, chucking balls at each other mid-drive. After logging probably 1,000+ hours on these go-carts in childhood, we ended up with zero major — or minor — injuries.

Yet, when I gave my son the “keys to the cart” I was fearful of every little action — every turn, every strong press of the gas pedal. I wanted to control, protect, and pad him at every move. Here I was applying the fear-based, overprotective parenting I knew was limiting him from learning. Here I was with a perfect chance to change.

On one side: It would be poor parenting to give an 8 year old unfettered access to tear up suburb streets on a go-cart.

On the other side: It would be poor parenting to micromanage every moment of an 8 year old learning to ride a go-cart.

Structured Freedom is a balance: Providing coaching and support to learn a skill followed by freedom and trust to apply the skill.

Putting knowledge into practice, I started with structure. For two weeks, I rode my bike alongside my son as he go-carted the streets, reminding him of the rules of the road and teaching him to scan and use caution. We’d debrief each ride. Each new round I’d let him get further and further ahead of me.

Then, it was time for the freedom. I’d give him the chance to go a short loop around the block, letting him know I’d come out to help if he didn’t make it back home within a set amount of time. We pre-briefed what he would do if he had any issues.

Now, he takes these rides solo. Sure, he drove over a curb once. He flew across some hard bumps and it killed the engine. He had the chain pop off a block away from home.

But here’s the beauty: He learned that driving over curbs hurts and he should probably not do it again. That going reckless on bumps kills the ride, literally. And that he is capable of re-attaching a go-cart chain if he needs to.

Most of all, I’m learning a critical truth: Kids don’t learn skills by listening to their parents or teachers describe the skills. They don’t master them in perfectly controlled settings. They learn them by practicing skills in contexts where risks are real but not devastating. Where adults are available but not required. Where opportunities have structure without suffocation.

Our world is not a bubble-wrapped utopia. But that doesn’t mean we need to bubble-wrap our kids. They are capable. They are born explorers and learners. They are anti-fragile. When it comes to the real world, sometimes we (I) need to get out of their way.

Leave a comment